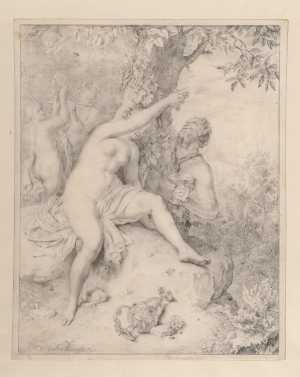

Specifications

| Title | Portrait of Michelangelo Buonarroti |

|---|---|

| Material and technique | Black and red chalk |

| Object type |

Drawing

> Two-dimensional object

> Art object

|

| Location | This object is in storage |

| Dimensions |

Height 367 mm Width 272 mm |

|---|---|

| Artists |

Draughtsman:

Fra Bartolommeo (Bartolomeo-Domenico di Paolo del Fattorino, Baccio della Porta)

|

| Accession number | I 563 N 181 (PK) |

| Credits | Loan Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (former Koenigs collection), 1940 |

| Department | Drawings & Prints |

| Acquisition date | 1940 |

| Creation date | in circa 1516-1517 |

| Collector | Collector / Franz Koenigs |

| Provenance | Fra Bartolommeo’s estate (1517); his heir Fra Paolino da Pistoia (1488-1547), Florence; Suor Plautilla Nelli (1523-1588), Florence; Convent of St. Catherine of Siena, Florence; Cavaliere Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri (1676-1742), Florence, acquired from the convent in 1725 and mounted in one of two albums (1729); Gabburri Heirs; Art dealer William Kent, London, bought from the Gabburri Heirs in 1758-60; Benjamin West (1783-1820, L.419), London; his son Raphael West; Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830, L.2445), London; Art dealer Samuel Woodburn (1781-1853, L.2584), London, acquired with the Lawrence Collection in 1834, cat. London 1836, seventh exhibition; The Prince of Orange, afterwards King William II of the Netherlands (1792-1849), The Hague, acquired in 1840; his sale, The Hague (De Vries, Roos, Brondgeest) 12.08.1850, lot 281 (unsold); his daughter Princess Sophie van Oranje-Nassau (1824-1897), Grand Duchess von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, Weimar; her husband Grand Duke Karl Alexander von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1818-1901) Weimar; their grandson Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1876-1923), Weimar; Franz W. Koenigs (1881-1941, L.1023a), Haarlem, acquired in 1923; D.G. van Beuningen (1877-1955), Rotterdam, acquired with the Koenigs Collection in 1940 and donated to Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

| Exhibitions | Rotterdam 2016 (Rondom Fra B.) |

| Internal exhibitions |

Rondom Fra Bartolommeo (2016) |

| Research |

Show research Italian Drawings 1400-1600 |

| Literature | Von Zahn 1870, p. 201; Knapp 1903, p. 312; Von der Gabelentz 1922, vol. 2, no. 842 (c. 1514-1515); Regteren Altena 1967, vol. 2, p. 167; Fischer 1990, p. 296, fig. 191; Fontana 2002, pp. 154-157; Goldner 2016, pp. 105-106, fig. 8; Elen 2019, p. 247 |

| Material | |

| Object | |

| Geographical origin | Italy > Southern Europe > Europe |

Do you have corrections or additional information about this work? Please, send us a message