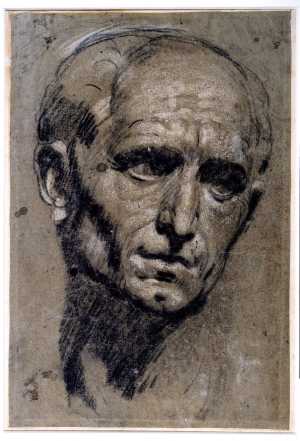

With no fewer than twenty drawings, Tintoretto was well represented in the collection of Franz Koenigs. This may well point to a conscious preference on part of the collector. Tintoretto made several studies after antique heads, including the bust represented here, which was given to the City of Venice by Cardinal Domenico Grimani in 1523 and was then believed to represent the Roman emperor Vitellius.

Study after a Bust of Julius Caesar by Simone Bianco

Jacopo Tintoretto (Jacopo Comin, Jacopo Robusti) (in circa 1570-1580)

Specifications

| Title | Study after a Bust of Julius Caesar by Simone Bianco |

|---|---|

| Material and technique | Black chalk, heightened with white, on discoloured blue paper, pen and brown ink, brown wash, on white prepared paper |

| Object type |

Drawing

> Two-dimensional object

> Art object

|

| Location | This object is in storage |

| Dimensions |

Width 229 mm Height 340 mm |

|---|---|

| Artists |

Draughtsman:

Jacopo Tintoretto (Jacopo Comin, Jacopo Robusti)

|

| Accession number | I 205 recto (PK) |

| Credits | Loan Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (former Koenigs collection), 1940 |

| Department | Drawings & Prints |

| Acquisition date | 1940 |

| Creation date | in circa 1570-1580 |

| Watermark | unidentifiable (below left, on P2 of 7P, vH) |

| Inscriptions | ‘G. Tintoretto’ (below left, pen and brown ink) |

| Collector | Collector / Franz Koenigs |

| Mark | Galleria A. Simonetti (L. 2288bis deest), F.W. Koenigs (L.1023a deest) |

| Provenance | (?) Attilio Simonetti (1843-1925), Galleria Simonetti, Rome (L.2288bis deest); Franz W. Koenigs (1881-1941, L.1023a), Haarlem, acquired in 1928 (?) from the Simonetti heir via art dealer Nicolaas Beets; D.G. van Beuningen (1877-1955), Rotterdam, acquired with the Koenigs Collection in 1940 and donated to Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

| Exhibitions | Amsterdam 1934, no. 676; Rotterdam 1938, no. 362; Paris 1952, no. 95; Rotterdam 1952, no. 95; Amsterdam 1953, no. T 62; Rotterdam 1957, no. 45; Paris/Rotterdam/Haarlem 1962, no. 115; Venice/Florence 1985, no. 35; Rotterdam/New York 1990, no. 67; Moscow 1995, no. 27; Florence 2000, no. 7; Rotterdam 2009 (coll 2 kw 1); Venice/Washington 2018 |

| Internal exhibitions |

Tekeningen uit eigen bezit, 1400-1800 (1952) Italiaanse tekeningen in Nederlands bezit (1962) Van Pisanello tot Cézanne (1992) De Collectie Twee - wissel I, Prenten & Tekeningen (2009) |

| External exhibitions |

Tintoretto 500 (2018) |

| Research |

Show research Italian Drawings 1400-1600 |

| Literature | Von Hadeln 1933, no. 11, pl. 8; Amsterdam 1934, no. 676; Rotterdam 1938, no. 362, pl. 238; Borenius 1934, p. 194; Rotterdam 1938, no. 362, fig. 238; Tietze/Tietze-Conrat 1944, no. 1663; Pallucchini 1950, p. 146; Paris 1952, no. 95; Cain/Vallery-Radot 1952, ill.; Haverkamp Begemann 1952, no. 95; Amsterdam 1953, no. T 62, pl. 66; Forlani 1956, p. 42, no. 71; Haverkamp Begemann 1957, no. 45, ill.; Forlani 1957, p. 86; Sidorov 1959, no. 46; Jaffé 1962, pp. 230, 234, fig. 1; Paris/Rotterdam/Haarlem 1962, no. 115, pl. 85; Meijer 1963, pp. 63-3f, 63-3b, fig. 1; Andrews 1968, p. 120, under no. D 1854; Pignatti 1970, p. 10; Rossi 1975, pp. 54, 62, fig. 5, fig. I (Roman digit, verso, JT?); Byam Shaw 1976, p. 206; Byam Shaw 1985, p. 832, fig. 121; Aikema/Meijer 1985, no. 35, ill.; Luijten/Meij 1990, no. 67, ill.; Moscow 1995, no. 27, ill.; Florence 2000, no. 7, ill.; Rearick 2001, p. 161; Dekker 2018, pp. 30-31, fig. 22; Venice/Washington 2018, pp. 175, 176, 264, fig. 153; Marciari 2018, p. 112 n. 13 |

| Material | |

| Object | |

| Technique |

Highlight

> Painting technique

> Technique

> Material and technique

|

| Geographical origin | Italy > Southern Europe > Europe |

| Place of manufacture | Venice > Veneto region > Italy > Southern Europe > Europe |

Do you have corrections or additional information about this work? Please, send us a message

Entry catalogue Italian Drawings 1400-1600

Author: Albert Elen

Jacopo Tintoretto involved his apprentices, including his son Domenico (1560-1635) and daughter Marietta Robusti (c.1554-1590), in drawing sessions in order to improve their skills in disegno. Sitting in a semi-circle, they used to draw after small-scale casts of antique and contemporary sculptures as still models, which were observed from different angles with a strong light source casting shadows.[1] In addition, they would study and copy existing drawings made earlier by the master himself, and even copies after such copies, sometimes working up offprints of chalk drawings. This explains the varying artistic quality of these drawings after sculptural models, which were unsigned and kept together in the heterogeneous workshop stock, and the resultant difficulty in distinguishing between Jacopo’s hand and that of his talented students. These drawings probably date from the time his children were in their teens, around 1570-80.[2]

The present double-sided sheet bears witness to this educational practice; it has two drawings of the same model, the one on the recto being an original by Jacopo, the other on the verso a weak copy, possibly even made after another copy of Jacopo’s example.[3] The sculptural model, now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Venice, was a small marble bust, purportedly of the Roman emperor Julius Caesar (100-44 BC), which was long supposed to be a classical sculpture but is now considered a contemporary marble bust all’antica by Simone Bianco (1480/1490-after 1533).[4] Bianco was a Tuscan sculptor, working in Venice in the 1530s and ‘40s and renowned among collectors in the Veneto and beyond for his classicizing portrait busts. Tintoretto must have had access to this bust when it was in the collection of the influential Venetian patrician Giacomo Contarini (1536-1601).[5] He may even have owned a cast of this sculpture, as was the case with a classical bust of the eighth Roman emperor, Vitellius (15-69 AD).[6]

Our recto drawing is the finest of a small group of five surviving drawings after the same sculpture, all confined to the head, and is the only one by Jacopo himself.[7] The heavy shadows, especially in the eye sockets, indicate that it was lit from above. The sensitivity with which the facial features are described, by heavily hatched shading in black chalk, combined with highlights in white, imbue the image with a remarkable quality of presence, as if the model were alive. Less convincing, though, is the indistinct rendering of the hair on the temples of the otherwise bald head. The drawing is stylistically close to several of Jacopo’s drawings after the Vitellius bust, of which over twenty survive.[8]

Footnotes

[1] Rearick 2001, pp. 160-61.

[2] Marciari 2018, p. 99.

[3] Remarked by John Marciari during a visit to the museum in September 2017. The verso was, on the other hand, referred to by Jaffé (1962) as ‘a splendid example of the master’s drawing after the same antique head as the recto, only at a slightly different angle and by another cast of light’.

[4] Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. N 50, 59 cm high; Luijten/Meij 1990, p. 187, fig. b; Venice/Washington 2018, pp. 175-76, fig. 154.

[5] Mentioned in the inventory of the Contarini Bequest of 1714 (bequeathed by Giacomo’s descendant Bertucci Contarini); Hochmann 1987, p. 485, no. 33 (as a modern copy); reproduced in an engraving by Giovanni Antonio Faldini in Anton Maria Zanetti’s Delle antiche statue greche e romane, che nell'antisala della Libreria di San Marco, e in altri luoghi pubblici di Venezia si trovano, vol. I, pl. I, Venice 1740 (online).

[6] This Roman sculpture was bequeathed by the cardinal Domenico Grimani to the Venetian Republic in 1523; it was on show in the Palazzo Ducale from 1525 and is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. N 20. According to Davis 1984a, p. 33, there are only two antique models used by Tintoretto, recorded in drawings: the bust of Caesar (no longer considered antique) and the head of the emperor Vitellius, to which the head of Laocoon (Vatican Museums) can be added (inv. I 69 and I 398, also from the Koenigs Collection, the latter now in Moscow; Elen 1989, no. 398; Moscow 1995, no. 127, ill.).

[7] Rossi (1975) and Rearick (2001) are the only scholars doubting the authenticity, the former putting a question mark and listing it with the ‘uncertain drawings’, the latter dubbing it ‘problematic’ without an explanation. The other drawings are in Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 17237 F r.; Tietze/Tietze-Conrat 1944, no. 1644, c.1580; Rossi 1975, p. 54 (workshop), Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, inv. D 1854, and London, British Museum, inv. 1913,0331.185.

[8] Including three in the Koenigs Collection, inv. I 340, I 341 (recto and verso); Elen 1989, no. 396; Moscow 1995, nos. 128, 129, ill. Other drawn versions of this model are in, among other collections, New York, Morgan Library & Museum, inv. 1959.17, and London, British Museum, five sheets, inv. 1885,0509.1656-1660; Rossi 2011, pp. 58-62, figs. 4-10 (all Domenico Tintoretto); Marciari 2018, pp. 98-101, figs. 68-72, who dates all to c.1570-80.