Yayoi Kusama - When the Unique Becomes a Multiple

An examination of the multiple variants of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show), (1965/1998)

Author: Machteld Verhulst

Please refer to this digital article with the following bibliographical citation:

Machteld Verhulst, When the Unique Becomes a Multiple, Rotterdam (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) 2022, accessed [date of access], https://www.boijmans.nl/en/collection/research/when-the-unique-becomes-a-multiple

Straight to

Introduction

The value of an artwork is determined by many different factors: the artist’s reputation, the work’s importance to a movement, whether it is critically acclaimed to be a good, beautiful, dynamic work and much more. Including whether or not the work is unique.

Yayoi Kusama (1929, Masumoto) is an artist with a great reputation, whose work is an important part of the American post-war landscape. Her work was critically acclaimed in the 1960s in New York and in Europe and, following a revaluation of her work in the 1990s, she has become one of the most famous contemporary artists in the world. Nowadays people line up to spend mere seconds in Kusama’s fully immersive Environments. These famous Infinity Mirror Rooms, many of which have been created in recent decades, have crowds all over the world swooning over their lively, colourful nature, which has made them an Instagram phenomenon. This is why it is no surprise that Kusama has become one the world’s most expensive living female artists. 1 Even now, in 2021 at the age of 91, Kusama is still making art, including new ‘Infinity Mirror Rooms’.2

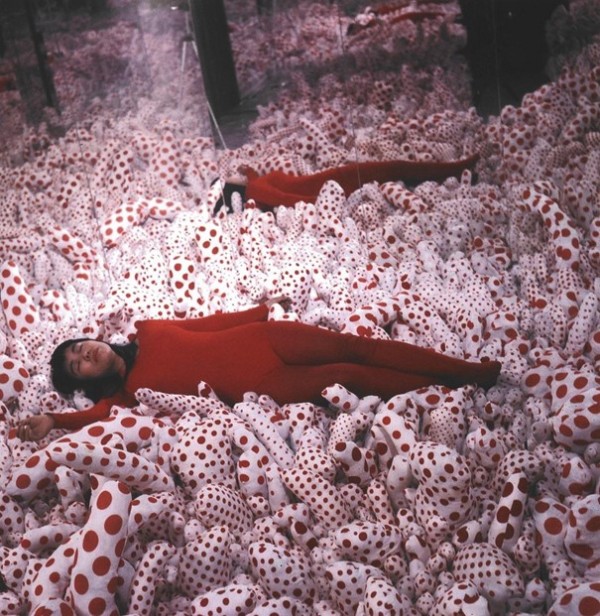

As is the case with much of Kusama’s contemporary work, the recent Infinity Rooms find their origin in the 1960s. In 1965 Kusama showed her first fully immersive Environment, Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) at the Castellane Gallery in New York. The work was a new direction for the artist, who had been playing with the concept of infinity throughout the late fifties and early sixties and whose most recent work was mainly soft sculpture.3 Kusama brought these concepts together in Phalli’s Field to create a space in which visitors could fully lose themselves as they were endlessly reflected between stuffed phalli covered with red polka dots. After Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) Kusama went on to experiment more with the use of mirrors in her work to allow her viewers to experience infinity.4

In the mid-1970s, Kusama retreated to her native country, Japan, for health reasons.5 She returned to New York in 1998 for a major retrospective of the works she created between 1958 and 1968, the first decade she spent in New York. The show was mounted by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Walker Art Centre.6

As part of the exhibition, Kusama recreated some of her seminal works from the 1960s. Among them was Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (fig. 1). The work, which was dated 1965-1998, brought back the type of work that has by now become the most famous part of her oeuvre, the Infinity Mirror Room. After the exhibition ended in 1999, Kusama kept creating new and different Infinity Mirror Rooms, many of which have toured the world in subsequent exhibitions and have been acquired by renowned museums for their collections. The same happened to Phalli’s Field (1965-1998). The work toured the world as part of an exhibition with stops in Rotterdam, Sydney and Wellington in 2008 and 2009. After the tour ended, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam was able to purchase the work.7

Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) has been on show almost permanently since its acquisition in 2010. As a result, it became a favourite of many of the museum’s national and international visitors and an icon of the collection. However, in 2013 another variant of Phalli’s Field showed up in the collection of the newly founded Fondation Louis Vuitton (FLV) in Paris. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen was not formally informed of this purchase by the Victoria Miro Gallery in London, through which they had bought their variant of the work in 2010. The staff was surprised to learn that a new variant of the work had been sold, since they had assumed that they had purchased a unique artwork. FLV purchased their new variant of the work, dated 1965/2013, through the same gallery as Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. FLV, however, were informed that the work they had bought was a multiple, one of three, and not a unique work of art.8 As is to be expected with a multiple, other variants of Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) besides the ones in the collection of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen and Foundation Louis Vuitton have surfaced since. One of the works, dated 1965/2016, was part of an exhibition that toured North America in 2016 and 2017. This work was acquired by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C. in 2016 before the show opened.9 As a result, Kusama’s seminal work is now a part of three museum collections.

This article examines what the creation, re-creation and subsequent sales of multiple variants of Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) by Yayoi Kusama mean for the 1998 variant of the work, which is part of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen’s collection.10 The existence of the newer variants of the work calls into question the status of the 1998 variant of the work in Kusama’s oeuvre, and its value. This article sets out to shed light on the relationship between the variants of the work and answers the question as to how the 1998 variant of Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) by Yayoi Kusama can be understood in relation to previously and subsequently created variants of this work. The article begins with an overview of the artist’s biography, with a specific focus on the years leading up to the creation of Phalli’s Field (1965), followed by a discussion of the different variants of the work; in conclusion the case is considered in the wider context of questions of originality, authenticity and the multiple.

It is important to note that in order to avoid confusion about which variant of the work is being discussed the titles of the works are shortened and the year of creation is added after it in brackets such as ‘(1965)’, ‘(1965-1998)’, ‘(1965/2013)’ and so forth; or ‘1998 variant’, ‘1965 variant’, and so forth will be used. In the case of the variants that were sold and are now part of a collection, mention of those collections will be made with the dates to further clarify which variants are being discussed. It is also necessary to set up the terminology that will be used in this article going forward. The reader may have noticed that the word that has been used in this article to describe the various Phalli’s Fields is ‘variant’. The decision to use ‘variant’ was made because ‘version’ does not fully or correctly encompass the relationship between the various works. ‘Version’, to me, implies an alteration or translation of sorts, like a book that has been translated or made into a movie. To apply ‘version’ to the case of Phalli’s Field, would create too much of a distance between the works. Whereas the word ‘variant’ more strongly implies that the two or multiple objects are nearly identical. An example that is used to define the word ‘variant’ is that of two different spellings of the same word, for example ‘neighbor’ and ‘neighbour’ or ‘gray’ and ‘grey’. The words carry the same meaning; they simply look slightly different. In this case ‘variant’ works best when describing the relationship between the various Phalli’s Fields and will be used throughout this article.

Biography

Yayoi Kusama was born in Matsumoto, Japan in 1929. From a young age she loved drawing and painting. Against her family’s wishes she aspired to be an artist.11 After many years of arguments, her mother finally allowed Kusama to move to Kyoto to attend art school. Kusama decided to quit art school after only one year, because she was dissatisfied with what she was learning.12 Around 1955 Kusama started to set her sights on America, specifically New York.13

Three years later, in 1958, Kusama got to New York after a stopover in Seattle. During her first years in New York, Kusama painted her now famous Infinity Net paintings. These often large paintings consisted of a single-colour background over which Kusama painted seemingly endless half circles, creating a net without beginning, end or centre. It was these paintings that brought Kusama to the attention of the New York art world. Art historian Midori Yamamura, who specializes in post-World War II Asian Art, notes that these works were Kusama’s response to the Action Painting that was dominating the scene at the time.14 In 1961 it seemed like Kusama’s career was taking off as she had several solo shows in various galleries along the East Coast and her work was included in various exhibitions in Europe.15 However, after this peak in success it would take another two-and-half years before Kusama had a solo show in New York.16

She did, however, participate in several group shows, including one at the Green Gallery in the summer of 1962.17 This particular show also featured works by Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg, amongst others. Kusama offered to show several collages as well as two of her Accumulation sculptures, an armchair and a couch.18 The exhibition of these works marked a new direction in Kusama’s oeuvre, as she had only recently moved from painting, through collage into sculpture.19 The Accumulation sculptures were everyday household objects that Kusama covered with white fabric stuffed phallus-like forms.20 When looking at these sculptures the viewer recognizes their shapes as something familiar, while at the same time the object looks foreign, overgrown with peculiar shapes. The use of fabrics to create these shapes led to them being dubbed ‘soft sculptures’.21 When the show ended, the owner of the Green Gallery, Richard Bellamy, offered Kusama a solo show at the end of the year. She had to decline the offer because she did not have enough money to make new work.22 At that time Kusama was very poor, often struggling to buy paints and other supplies.23 Because she declined, Bellamy invited Claes Oldenburg to take the slot instead.24 Months later, when the show opened, Kusama attended the opening night. She was shocked to find that Oldenburg was showing soft sculptures, just like her Accumulation sculptures.25 Oldenburg had not previously ventured into using textiles for his sculptures, and Kusama became convinced that, having seen her work months before, he had stolen her ideas.26

Based on statements made by Donald Judd and other artists who knew Kusama at the time, it is believed that she became increasingly paranoid that others would steal her ideas as well. This supposedly led her to cover the windows in her studio facing Park Avenue and 19th Street.27 It was during this time that Kusama was working hard on little money. Although she was receiving critical acclaim for her work, she was not selling much, which made her feel as though she was not getting any real recognition for her work.28 All the while white, male, American artists like Warhol, Oldenburg, Judd and Frank Stella were showing and selling their work all over New York.29 According to art historian Midori Yamamura, who has frequently written about Kusama, this sent Kusama into a downward spiral, which eventually led her to be admitted to a local hospital after suffering a nervous breakdown. When she came out of hospital, she started seeing a psychiatrist and taking medication.30

Throughout the early to mid-1960s Kusama kept creating Accumulation sculptures. In 1963, Kusama showed one of her now most famous works from the Accumulation series called One Thousand Boats Show (1963) (fig. 2). The work was created for an exhibition at the Gertrude Stein Gallery in New York and consists of a room filling Environment of a rowboat covered in white phalli, placed in a space that is covered from floor to ceiling by 999 photographs of the same image of the rowboat.31 After the success of the show, Kusama made a deal to do three solo shows at the Castellane Gallery: one in 1964, one in 1965, and one in 1966.32 Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) debuted in the second show in 1965.

During this time Kusama started to establish a reputation in Europe. She had exhibited at several galleries in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague.33 In The Hague she had several shows throughout the 1960s at Internationale Galerie Orez.34 She participated in several group exhibitions, including the seminal ‘Nul’ exhibition at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1965, where her work was shown alongside that of prominent artists of the Dutch ZERO movement like Jan Schoonhoven and Henk Peeters as well as that of Lucio Fontana and Hans Haacke. Kusama became close friends with some of these artists and they came to support her and her work in later years, like Schoonhoven who participated in her Happenings in Schiedam and Delft in 196735 and Fontana who supported her in her participation at the 1966 Venice Biennale, connected her with his gallerist and made sure she had a studio to work in whenever she was in Italy.36

Despite her success in the 1960s, over time Kusama fell out of the public eye in the New York art scene.37 She eventually had to retreat to her native country Japan in the mid-1970s due to health reasons.38 In Japan Kusama was more infamous than famous. She kept working on her art and had several national and a few international exhibitions, most of them group shows and almost all of them in galleries, in the late 1970s, throughout the 1980s and the early 1990s. In the late 1990s she had a resurgence in popularity in the Western art world and her work started to be shown in some well-known museums.39

Variants

Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965)

The Infinity Mirror Room was a new direction for Kusama, as it was her first fully immersive Environment but brought together themes and techniques from her earlier work. The concept of the infinite was previously visible in the Infinity Net paintings and the use of fabric to create sculpture was evident in the Accumulation works that Kusama was still producing at the time Phalli’s Field was created.

Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965) was meant to fully envelop and immerse the viewer. Kusama wanted visitors to ‘walk barefoot through the phallus meadow becoming one with the work and experiencing their own figures and movements as part of the sculpture’.40 Although Kusama never clearly states what she means with her individual works, Phalli’s Field (1965) can be looked at through the lens of the more general themes in her work. The title of the work, Phalli’s Field, conjures up associations with the phallic and a larger theme of sex. This theme was already present visually in the earlier Accumulation sculptures but in Phalli’s Field (1965) it was made more explicit. Kusama talked about her use of phallic shapes, saying: by continuously reproducing the forms of things that terrify me, I am able to suppress the fear. I make a pile of soft sculpture penises and lie down among them. That turns the frightening thing into something funny, something amusing.41

Unlike the earlier Accumulation sculptures, the phalli are covered in dots. According to art historian Jodie Cutler, the dots on the phalli should be understood as a suggestion of disease, because Kusama has mentioned that her fear of sex is partially derived from a fear of venereal diseases.42 Art historian and avid writer on Kusama, Midori Yoshimoto, states that the specific diseases Kusama was afraid of were syphilis and gonorrhoea. Yoshimoto further claims that with the mirrors in Phalli’s Field (1965), Kusama intended to create what was supposed to be a ‘field of sex’.43 The repetitions that the mirrors create and surrounding herself with the things she fears most was a way for Kusama to curb her fear and anxieties. In the case of Phalli’s Field (1965), the fear she was fighting was a fear of sex.44

Beyond the theme of sex, and Kusama’s fears around it, scholars like Yoshimoto have pointed Phalli’s Field as a reflection of Kusama’s desire to become one with her work.45 Kusama herself has gone beyond this stating that with Phalli’s Field (1965) she wished to show that she was ‘one of the elements – one of the dots among the millions of dots in the universe’,46 an idea which she calls ‘self-obliteration’.

Art historian Jo Applin, who has dedicated an entire book to Phalli’s Field (1965), focused on the themes and ideas behind it. In it, Applin endeavours to push our reading of the work beyond a mere representation of Kusama’s inner world, stating: Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli’s Field speaks to an engagement with the world at large, and the relations that occur within it.47

Applin focuses her reading of the work on its ambiguities, stating that ‘friction’ is the word that best describes this and some of Kusama’s other works.48 Applin quotes an especially poignant statement about this work by Claire Bishop, who said that the work is experienced by viewers as either ‘oceanic bliss’ or ‘claustrophobic horror’49 – making the work into what Applin calls ‘a world in which conflicting webs of relationships were generated and resolved, invoked playfully and mapped spatially’.50 In the end, Applin concludes that there was no single point that Kusama tried to make with this work. In fact, she believes that it was deliberately kept open-ended, in order to challenge the visitor to shape and be shaped by the work.51

Few images of the original Phalli’s Field (1965) have survived and, like many of the photographs of Kusama’s works taken at the time, all but one of them feature the artist herself.52 Photographs of this work show Kusama, either lying or standing among the spotted phalli, wearing a bright red leotard as she is endlessly reflected in the mirrors surrounding her (fig. 3) Like the original work, all the photographs taken of it succeed in disorienting the viewer and it is only when one sees the technical drawing of the work (figs. 4a and 4b) that its shape and inner workings become clearer. It is here that we clearly see that the original variant of Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965) was not a perfect square but an asymmetrical octagon. The corners of the mirror walls were flattened to create an octagonal shape, probably to enhance the number of reflections that visitors could see of themselves as the extra corner created more, and more interesting, angles.

The drawing also shows that there was a path through the installation, with an entrance and an exit on opposite sides of the room. This can be seen in the technical drawing of Phalli’s Field, and in a lesser-known photograph taken of Kusama inside the work (fig. 5). In this image more of Phalli’s Field is visible because of Kusama’s position in the middle of the work. The camera can be seen in the reflection of the mirrors behind Kusama as can the separate entrance and exit. There are two spots in the photograph where there is no mirror, on the right side in the reflection and all the way in the top left corner in the reflection. This is in line with the placement of the entrance and exit in the drawing. One might argue that because of the reflections it cannot be said for sure that the entrance and exit are separate. Though this may be true of several other images taken of the work, it is not the case with this one. When looking at the entrance on the right and exit on the left it is interesting to note that there seems to be some kind of object positioned on the path on the right side. On the left we see the camera on the tripod, whereas on the right we see something else. Something smaller and wider than the tripod and black, unlike the silver grey of the tripod. It looks like a stool of some sort. At any rate, what this image further confirms is that the path within the work is a U-shape and that there is a separate entrance and exit. After all, if the separate entrance and exit was an illusion created by the mirrors, there would be two tripods with a camera on them visible in this photo.

Besides this image, there are photographs taken before the installation of the work at the Castellane Gallery as well as others from the years after the exhibition that confirm this layout. An image of Kusama in her studio taken by photographer Eikoh Hosoe shows the artist leaning against one of the floorboards from Phalli’s Field (1965), with several other boards in the background (fig. 6). This image, which was taken prior to the show at the Castellane Gallery, shows that the floor elements were not all square nor were they the same size. In the background on the left we see a floor element in the shape of a long rectangle leaning against a window. One of the corners of the rectangle has been chamfered to fit into the octagonal room. This piece can be seen in the bottom right corner of the technical drawing (figs. 4a and 4b).

In the same vein there are also photographs of the floorboards being used after the 1965 exhibition of Phalli’s Field which further confirm that the shape of the installation is in line with the technical drawing. In the photographs taken of 14th Street Happening (1966) (fig. 7), Kusama can be seen lying on one of the floorboards. Again, this particular board is a rectangle. Once more, looking at the technical drawing of the work we can see a board of a similar shape and size on the drawing. Taking all this into account, there is no reason to doubt the technical drawing of the work; we can therefore confirm that Phalli’s Field (1965) was an octagonal shape, had a separate entrance and exit and a path to walk through it.

As we have seen, elements of the work remained in use for happenings after the show at the Castellane Gallery had finished. After 1968 the floor panels do not appear in any photographs of Kusama’s Happenings. It is likely that they were destroyed, possibly because they were damaged or dirty as a result of frequent use.

The recreation of 'Phalli’s Field' in 1998

In mid-1990s, after years of showing mostly in group shows in galleries in Japan and some in America and Europe, Kusama began to get more and more critical acclaim.53 This came to a head in 1998, when a large retrospective of Kusama’s works from her first ten years in New York was mounted by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), MoMA and the Walker Art Center. The exhibition toured all three institutions and included a, for Kusama, glorious return to New York for the first time in over twenty years.54

The show, titled Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama, 1958-1968, featured Infinity Net paintings, Accumulation sculptures and a remake of Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show). The exhibition was mounted by curators Lynn Zelevansky (LACMA) and Laura Hoptman (MoMA). Zelevansky had only just left New York to work at LACMA when she first pitched the idea of a Kusama retrospective, an idea she had had for five years.55 She had always been aware of Kusama’s work as, she said, Kusama was still quite well known in the New York art world in the 1990s.56 Zelevansky and Hoptman worked closely together with Kusama and her studio in Japan to mount the show.57 The selected works were proposed by the curators and approved by Kusama. According to Zelevansky, the artist was open to everything because she really wanted the show to happen.58 The list of proposed works included pieces like Phalli’s Field (1965), which had to be re-created since they were no longer extant. For the re-creation of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) the studio and the people at LACMA worked together on the design, sending sketches of the space back and forth via fax from late 1997 and throughout 1998.59 Although in some regards the re-creation was a true collaboration, Zelevansky stresses that it was Kusama who had the final say (fig. 8).60

Faxes in the LACMA archives indicate that the fabrication of the work was also a collaboration.61 The room was fabricated by the technical team at LACMA, who were also responsible for the mirrors. Kusama created the phalli covered floorboards in her studio in Japan and they were flown out to Los Angeles with some of the other works featured in the show.62 The work was put together on site.

The 1998 variant of the work, which is officially dated ‘1965-1998’, is similar to the original work in many ways. The mirrors, the phalli and use of the red on white dotted fabric remained, as well as the use of various fabrics with different dot patterns – some close together, some further apart and some with bigger dots than the others. The open ceiling also remained the same. Nevertheless, the variant differs from the original work in various ways. First of all, the remake of the room was perfectly square. This was probably the result of the decision to make the floor panels square and exactly the same size – another divergence from the original. Most importantly, the work has only one door, which functions as both entrance and exit. Unlike the original work, it does not feature a path through the work, but rather a catwalk on which the viewer can stand. Lastly, the viewer is no longer allowed to enter the work by walking through the phalli, as Kusama originally intended and was part of the exhibition of the first variant of work at the Castellane Gallery in 1965. The viewer has to stay on the landing and cannot cross into the field of phalli.

This new variant of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) travelled across America in 1998 and 1999 and had a final stop at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo before it went back to the Kusama studio.63 A year later, in 2000, Phalli’s Field (1965-1988) was exhibited at the Sydney Biennale. There it was shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art. In Sydney, Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) was presented in the corner of one of the exhibition spaces in the museum, while most of the space was walled off. When you entered the hall, half of it was filled with the work, the other half was empty, so visitors could queue to enter Phalli’s Field (1965-1998).64 According to the communication between Kusama and the Sydney Biennale organization, there was an issue with the ceiling in the exhibition space. There was a beam that would cross right above the work.65 So instead of having an unobstructed view of the ceiling the beam would be in the way, which would distract from the work. It was decided to add a lowered cloth ceiling underneath the beam with lights directly above.66

'Phalli’s Field' (1965–1998) at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

In 2008 Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) was a part of a travelling solo exhibition on Yayoi Kusama mounted by Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen called Mirrored Years. The show included works from Kusama’s time in New York as well as some of her recent work. Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) was one of the biggest attractions in the show. The work was integrated into the space behind a wall (fig. 9). If the door to the work was closed, the visitor would not immediately notice it. When the visitor opened the door and stepped through, it would feel like entering another dimension.

In the presentation of the work in the ‘Mirrored Years’ exhibition, a semi-transparent fabric ceiling like the one in Sydney was added. This addition was made at the request of the studio.67 It is likely that it was deemed necessary to add the ceiling as a result of the placement of the work in the exhibition. With the work fully concealed behind a floor to ceiling wall, this would lead to what would have looked like a large shaft going straight up to the five-metre-high ceilings of the exhibition space at the Bodon wing in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. This shaft would have detracted from the viewers’ experience of the work once inside. The addition of the ceiling ensured that the proportions of the work were correct.

In 2010 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen was able to purchase the installation from the Kusama Studio through the Victoria Miro gallery in London.68 After the work was purchased, it was presented first in the museum’s main building (the Van der Steur wing) in a small exhibition specially mounted on the occasion of the purchase. Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) was installed in the middle of the exhibition space, as a white cube in a grey room (fig. 10), almost as if an alien object had landed in the room from outer space. When the door was closed the cube looked unassuming, concealing the hidden world within. With Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) now in the middle of a room as opposed to a presentation in a separate room. a ceiling was added to the work once more – again, made up of a wooden frame covered in cheesecloth.69 The lights on the ceiling of the exhibition space, several metres above the semi-transparent ceiling over the top of the room created diffuse and atmospheric lighting in the room itself. In 2011 Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) was reinstalled in the museum, this time on the ground floor of the Bodon Wing near the entrance area. It was exhibited there until the museum closed for renovation in 2019.70

After Phalli’s Field (1965–1998) was purchased by Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in 2010 it became an important icon for the museum’s collection. As a result, it was on show permanently and has never been loaned to any other institution. The museum believed it had bought the only extant variant of the work and had no reason to suspect the status of the work as such would change. This, however, turned out not to be the case. After 2010, Phalli’s Field would be re-created at least three times up to the time of writing. Variants of the work have since travelled all over the world as a part of touring exhibitions and, as we have seen, have been purchased by Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C. The more recent variants of Phalli’s Field will be discussed below and are split into two categories; variants of the work that have been sold and variants that have not been sold.

Sold variants

Fondation Louis Vuitton: Phalli’s Field (1965/2013)

Early in 2013, Sjarel Ex, the director of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, was informed by Suzanne Pagé, director of Fondation Louis Vuitton (FLV), that they had purchased a work entitled Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965/2013) through the London branch of the Victoria Miro gallery, the same gallery through which Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen had purchased its Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) three years earlier. Pagé also informed Ex that FLV had been told by the gallery that the work it had purchased was part of an edition of three, but not what number. In response to this Ex wrote a letter to the director of the Victoria Miro gallery asking him to clarify what had happened, because the museum believed it had purchased a unique work. There was no response.71 It has since become clear that the work in the FLV collection is number 2 out of an edition of three.72 This has recently been confirmed by the Kusama studio.73

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden: Phalli’s Field (1965/2016)

In 2016 the Hirshhorn Museum was the organizing institution of a travelling exhibition of Kusama’s work called Infinity Mirrors. The show started at the Hirshhorn and subsequently travelled to the Seattle Art Museum, The Broad, Art Gallery of Ontario, Cleveland Museum of Art, High Museum of Art. While the Hirshhorn was in the process of mounting the exhibition in 2016, the director of the museum, Melissa Chiu, informed the studio that they were interested in purchasing an Infinity Mirror Room. The Kusama studio replied that it had an edition of Phalli’s Field available, making it clear once again, as they had with the sale of the work to Fondation Louis Vuitton, that the work was an edition. It was only upon the purchase of the work that it went into production.74 This resulted in Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965/2016). However, the purchase of the work was not announced until March of 2019 in an online article on The Art Newspaper website.75 This time the staff at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen found out about the sale the same way everybody else did, through this article.

Unsold variants

Fondation Louis Vuitton and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden purchased new variants of Phalli’s Field, however there are several other institutions that only exhibited a variant of the work. Initially, when looking into this, it seemed that there have been at least two different variants of Phalli’s Field that have been exhibited worldwide, with a possible third variant to be shown in 2021. It seems as though there are multiple other variants because these works were all dated differently. The work in the collection of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen is dated ‘1965-1998’. The work in the collection of Fondation Louis Vuitton is dated ‘1965/2013’ and the work in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden is dated ‘1965/2016’. This means that any works with the same title, but with dates that deviate from the dates of works in the previously mentioned collections, must be other variants.

In 2013 and 2014, a variant of Phalli’s Field was part of a touring exhibition in South America and Mexico called Yayoi Kusama. Obsessão Infinita initiated by Instituto Tomie Ohtake.76 This work was dated ‘1965/2013’, the same as the work in the collection of Fondation Louis Vuitton. However, the exhibition catalogue states that the work was on loan from the collection of the artist.77 It is not likely that this work is the one that eventually became a part of the Fondation Louis Vuitton collection because they purchased the work before the exhibition in South America and Mexico opened. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark was the institution that opened the touring exhibition Yayoi Kusama: In Infinity in 2015.78 The exhibition featured a variant of Phalli’s Field dated ‘1965/2015’. The catalogue created for the exhibition stated that the work is part of the collection of the artist.79

Recently, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen received a request from the Martin-Gropius-Bau to lend several works from the collection for a touring exhibition that was originally supposed to take place in 2020 and 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic ultimately meant that the exhibition dates had to change. Among the works requested was Phalli’s Field (1965-1998). The staff at the museum declined the request, citing the need for a rigorous conservation of the work.80 The contact at the Martin-Gropius-Bau responded by letting the museum know that due to the decline it would pursue its other option of borrowing an exhibition copy of the work through the artist’s studio.81

As of now, it seems that we know of at least two – possibly three – other variants of Phalli’s Field beyond ones that are a part of collections. According to the studio, this is incorrect. In early 2021, the staff at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, together with the author, sent a list of questions to Yayoi Kusama’s studio in which we asked them, amongst other things, to clear up the situation around these different variants. The Kusama studio claims that the work that was shown in both the Yayoi Kusama. Obsessão Infinita and the Yayoi Kusama: In Infinity exhibition is exactly the same work, namely an artist’s proof.82 This is possible, because the exhibitions did not overlap, but it does not explain why they changed the date of the work to ‘1965/2015’ when it moved to Scandinavia – unless the work shown in South America and Mexico was destroyed; however, they claim that this is not the case.83

Differences between the variants

From the descriptions that have been given above of both the 1965 and the 1965-1998 variant of Phalli’s Field it may have already become clear that the works are by no means exactly the same. The first variant of the work that was on show at the Castellane Gallery in 1965 was an octagonal space, whereas the 1965-1998 variant of Phalli’s Field is a perfect square. Furthermore, technical drawings of the 1965 work have shown that the work has a path that goes through the work. As a result of this, the 1965 work had a separate entrance and exit. We know that the 1965-1998 work only has one opening that is used as both an entrance and an exit, and that there is no path through the work, only a short catwalk to the middle of the work. The differences between these works are quite apparent. This is not the case when one compares Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) with the newer variants of the work created after 2010.

At first glance, when looking at photographs of each of the extant variants of Phalli’s Field, there seem to be no clear differences between the works. Determining whether the arrangement of the floorboards with the phalli is different between the various works is very difficult to do. Even if a pattern of sorts is used for the arrangement of the phalli on the individual floorboards, there is no way of knowing if the way the crates are ordered in each of the different variants of the work is the same without looking at photos of the individual crates that make up every work. A different arrangement of the boards can make the works look vastly different even if the same pattern is used for every one of them. Nevertheless, there are other factors to be looked at that can help determine differences between the variants of the work.

By simply looking at the images of the different works and comparing them to the work in the collection of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, one can determine that the fabric used on the catwalk is different from all other new variants of the work that have been created from 2013 onwards. The print on the fabric on the landing of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) has dots in two different sizes whereas the print on the fabric of the landing in the variants dated 2013 and onwards has dots in only one size. The pattern of dots on the path in the first variant of Phalli’s Field (1965) is the same as those in the work created after 2010. This connects the newer variants of the works directly with the 1965 original and makes the 1965-1998 variant stand out.

Beyond the pattern of the fabrics used for the catwalk, the interior dimensions of the rooms differ slightly. The 1998 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen collection variant of the work is 460 x 460 x 250 cm whereas the 2013 FLV variant is 455 x 455 x 250 cm.84 The 2016 Hirshhorn variant of the work has the same dimensions as the 1998 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen variant, 460 x 460 x 250.85 The minimal difference of five centimetres in the dimensions of the floor space is translated to a difference of 0.5 centimetres in the dimensions of the phalli filled floorboards. Where the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen boards are 91 x 91 cm, the FLV boards are 90.5 x 90.5 cm.

Lastly it is noteworthy that the ceiling that was added to the 1965-1998 work as a result of the circumstances surrounding the 2000 presentation at the Sydney Biennale has since become a staple of the new Phalli’s Field post-2010, and the other Infinity Mirror Rooms for that matter. Not only has the work never been presented without it at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, it also seems to be a requirement of the post-2010 variants of the work. The installation instructions for the work on file at FLV state that a ceiling has to be added,86 and none of the currently extant variants of the work has been photographed without one since 2008. The studio has since confirmed that the work cannot be shown without a ceiling any more.87

Multiples

Questions of originality and authenticity

The main questions we should be asking in regard to Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) are: is the work original? And is the work authentic? When we know more about Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) it enables us to better understand the way this variant of the work relates to the others. An artwork’s status as an original is usually only questioned when there is a suggestion that it might be a copy or a facsimile. When it comes to Phalli’s Field (1965-1998), the question of its status as an original work depends on its relationship to the other Phalli’s Fields that exist and have existed. In this case, because Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) is derived from the 1965 work that is no longer extant, the question thus becomes: is the 1965-1998 work a copy of the 1965 work or an original artwork?

The 1965 variant of the work is no longer extant and as such the documentation that survives of it is the only thing with which we can define it. As I pointed out above, it was determined that the layout of the original 1965 work was different from the subsequent 1965-1998 work. The modification from an octagonal to a square layout may seem small and insignificant but is actually essential, since it drastically changes the experience of the work. Originally the viewer was able to move through it from one end to the other, allowing active participation in the work. By contrast, the catwalk that the visitor is allowed to walk on in Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) constrains their movement, with barely any space to walk around. Not only does the limited space constrain the viewer in the 1965-1998 work, they are also not allowed to walk between the phalli themselves. In the 1965 variant, where this was the case, they were therefore able to more fully immerse themself in the environment as they actively interacted with the work.88 In the 1965-1998 variant, the visitor is not only more constricted in their movement, but, unlike the original, the entrance of the work becomes invisible once the door is closed, which strengthens the sense of infinity.

The 1965-1998 work has lost some of the experimental and experiential qualities of the 1965 original. This shift is not completely unexpected as the remake of the work in 1965-1998 falls into a trend of the institutionalization of installation art in the 1990s.89 Museums at that time began collecting installation art and working with artists to recreate works from the 1960s and 1970s to give these originally temporary works a more permanent status. Like Phalli’s Field, most of these works were no longer extant and had to be re-created so they could be shown again. The re-creation of Phalli’s Field was accompanied by the layout change, making it easier for the work to travel and easier to re-install.90

From a marketing and sales standpoint, the change in layout from Phalli’s Field (1965) to Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) also greatly impacted Kusama and her career. With the concept of the ‘Infinity Mirror Room’ in this new shape it was repeatable, and the artist and her studio were able to make it into something easily recognizable. Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) paved the way for Kusama to create many more – and ever more elaborate – Infinity Mirror Rooms with different themes. Each of the works has the same square shape as Phalli’s Field (1965-1998), with mirrors covering the walls from top to bottom, with a single door that functions as both entrance and exit and a catwalk that extends to the middle of the room. An early example is Infinity Mirror Room - Fireflies on the Water (2002) (fig.11), in which Kusama chose to create a dark room to make the visitor feel as though there is no end to the space they are in. After Fireflies on the Water (2002), dark Infinity Mirror Rooms have become the staple. Kusama has created almost a dozen of them – the vast majority of the Infinity Mirror Rooms the artist has created since the late 1990s.91These dark rooms always feature some kind of twinkling lights inside, reflected in the mirrors on the walls and a basin of water or glossy black floors around the catwalk.

What this line of argument shows is that Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) has its own distinct character that is different from the 1965 work. Phalli’s Field (1965) can be placed in a tradition of larger overarching developments of art history in the 1960s, it can be linked to what was going on in New York at the time of its creation, and it tells a story about the point in her career Kusama was at when it was made. In the re-creation of the work in 1998, the layout was changed and with it the experience of the work. It lost its original experimental and experiential nature and was therefore changed irrevocably into something new: in fact, a different work entirely. This new work, which, however, bears the same title, also has its own place in art history: it too tells a story of its time and it too tells a story about the point Kusama was at in her career at the moment it was created. They are just different stories. Beyond all the similarities and differences, it is ultimately undeniable that the creation of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) changed the trajectory of Kusama’s career, as it became the blueprint for a distinctly recognizable concept that she is well known for all over the world today. Thus, it can be argued that Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) should be regarded as a separate, new, and therefore original artwork. Consequently, going forward in this article the Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) will be marked as ‘(1998)’ instead of ‘(1965-1998)’.92

At this point the reader might ask: you have just said that it is a new work, therefore is it not automatically authentic? Although this notion is not incorrect, it is nonetheless important to take a more in depth look at authenticity in the context of Phalli’s Field (1998). In his seminal essay Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility (1935), Walter Benjamin talks about the concept of authenticity and what an artwork needs to be authentic. Although Benjamin wrote this text at a time when installation art did not exist, his work has been the basis for much of contemporary art theory on authenticity. According to Benjamin, a work can only be authentic when it is original, because the original has tethers to a specific place and time. Furthermore, he notes that the authenticity of the work is its essence as it captures every aspect of the work’s history, including changes in ownership and alterations to the physical state of the work. A work of art is essentially a testimony of a certain history. When reproductions of artworks are made, they threaten the original’s authority to properly tell that story. Reproduction of a certain object breaks the bond that object has to the domain of tradition. The place of the object within the domain of tradition is what makes it original, and a work of art can only be authentic if it is original.93

Since Benjamin, many scholars have written about and critiqued notions of authenticity in relation to art. Questions of authenticity remain ever present in the day-to-day work of those tasked with preserving artworks for future generations. As such, the discourse around authenticity has grown and changed over the years. With this major discourse on authenticity comes a more in-depth investigation. As a result, authenticity has been split up into different categories, focusing on different aspects of an artwork. In her book Zo goed als oud (1993) Nicole Ex gives an overview of these different types of authenticity, describing what they entail and how they may influence a scholar or curator in the way they think about an artwork. In her book Ex discusses material, conceptual, contextual or functional, historic and a-historic authenticity.94The most interesting of these are a-historic and historic authenticities that focus on whether or not the full life of the artwork is visible in the here and now. For instance, if a painting was damaged during an attack of historical significance, one might choose not to restore it so as to show the life of the painting and to tell the story behind why it was damaged. This is considered a form of historic authenticity.95

Different forms of authenticity may sometimes coexist and may clash at other times. It is consequently important to consider what is most valuable about the object that one wishes to preserve, and to think about which point in the work’s history one wants to return to.96 Opinions about this can change over time and it is therefore important to realize that what we value now is a snapshot of a moment in time. More recently, scholars such as Vivian van Saaze have started thinking about authenticity as a process. Van Saaze specifically speaks of authenticity as something that is actively done within institutions. According to her, authenticity is made through museum practices by which works of art are continually re-evaluated and reinterpreted.97 Pursuing this thought, Van Saaze argues that authenticity can be ‘done’ and that it is something that can be manufactured.98 In her book on installation art, Van Saaze describes the case of Nam June Paik’s One Candle (1988). This work has been part of the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK) collection in Frankfurt am Main for many years. Since the museum purchased the work, the staff believed they had the only ‘real’ work in their collection. As Van Saaze notes, there are in fact multiple works that look like One Candle, all of them by Paik.99 Through their practices, however, the MMK keeps up the singularity of the work in their collection.100 Essentially, acting as though they possess the only authentic One Candle (1988).

It can be argued that Phalli’s Field (1998) is an authentic work of art. Not simply in the way in which we consider authenticity today, but from Benjamin onwards. According to Benjamin, a work must be original to be authentic; because we consider Phalli’s Field (1998) an original with its own place in time and tradition it must therefore be authentic. The work can also be read as authentic in the context of Ex’s various forms of authenticity, specifically materially and contextually. The phalli in the 1998 work that were made by Kusama are still the ones that are used today and the requirements for installation have stayed the same. Contextually the 1998 work is also authentic because it was created specifically to be shown in a museum, and it still is today. The dimensions and components of the work were made to fit within the museum apparatus, as it is easy to build up, break down, store and transport.

In line with more contemporary readings of authenticity, the status of Phalli’s Field (1998) as an authentic work becomes more contentious. The notion that a work is made authentic through practice lends itself to broad interpretation of the meaning of authenticity at any given time. Prior to this research, little was known about Phalli’s Field (1998) in relation to the other variants of the work and as a result the originality and authenticity were called into question. As a result of the creation and sales of the post-2010 variants of the work, the perceived authenticity of the 1998 variant was diminished. The knowledge about Phalli’s Field (1998) gained through this research has made available more information that will make it possible to grow confidence in the authenticity of 1998 work and thus grow its status as an authentic work.

Questions of unique and multiple

The majority of Kusama’s work is based in repetition, from her Infinity Net Paintings, in which she repeated the same brushstrokes to create a seemingly endless pattern, to her collages like Air Mail – Accumulation (1963) and her Accumulation sculptures. Multiplication has been at the forefront for many years. When Kusama was based in New York this was to do with patterns, shapes and the overall visual language of her work – something she is known for to this day. Since the late nineties and early zeroes, this has been further enforced as more of the works Kusama has recently created are multiples. This is reflected in both the newer Infinity Mirror Rooms and the inception of editioned prints and sculptures, for example her famous yellow and black polka dotted pumpkins.

When, or even before, a work of art is first created, an artist often decides whether it will be a unique work of which only one will be made or whether it will be a multiple, editioned work of art of which several or maybe even an unknown amount will be created. Examples of this are often seen in photography, bronze sculptures, design, and prints. The history of the multiple is in many ways tied to the history of printmaking. Even to this day, many of the multiples created are graphic works. Lithography is a good example of a type of technique that shows what printmaking was primarily about – namely, copying. Prints and printmaking techniques were used to make copies of text or images with the goal of making them more widely available, as with posters, but throughout history artists have also used it as an autonomous artform.101

This same idea of making things available for the masses was later adopted by twentieth-century pop artists who wanted to democratize the art scene and make their works more widely available to a bigger audience. In so doing, they revolted against the market that was based on original and unique artworks. By using graphic techniques such as silk-screening, the same image could be easily reproduced and distributed to a large group of people, thereby changing the way art circulated in the world. Multiples were more accessible to collectors and non-collectors who did not have a lot of money to spend on a unique artwork.102 These works were cheaper because they were much less scarce than unique works. One of the most famous examples of widely available works in the 1960s were Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup works. By creating them directly for the market Warhol demystified previously dominant ideas about uniqueness of works of art. Many pop artists went beyond printmaking and made multiples in the form of books, clothing, wallpaper and jewellery to name a few.103

To this day, the ideas of affordability and wider distribution are at the heart of the reason why artists make multiples. It is also an opportunity for artists to experiment with different styles and techniques or a way to shape a certain idea that could not have worked in any other form. It is difficult to create a succinct definition of the multiple. According to Stephen Bury, this is in part because artists often purposely push the boundaries of what can and cannot be considered a multiple.104 Consequently, a multiple can be many things and even the number or edition size seems to be irrelevant. What seems to be the most important to a multiple is the artists’ intention and execution.105 It can be executed in any medium or number they may feel appropriate.

Although multiples give artists a lot of freedom to create, there are still ‘rules’ in place that constrain the works and make them suitable for the market. These are aspects that tie the individual editioned works within the multiple together, such as the dating of the works, the number of works within a multiple and the fact that they look generally similar. For example, a single editioned lithograph within a multiple of fifteen might look slightly different from the others because the ink took to the stone differently, resulting in a thicker line here and there, but that does not change the work.

As was stated above, it is common for artists to actively choose to create a multiple. Less common, however, are cases in which a work of art that was once considered to be unique becomes a multiple later on. The exception to this is film and video art which, along with photography, is in some ways less regulated than other multiples. These works are often easily reproducible many years after their initial inception. For both film and video works, reproduction is necessary for their survival. The rapid evolution of technology means that carriers of a work can become unusable after a decade or less. When the earlier carriers are kept, the work is essentially multiplied and changes from a unique work into a multiple. It is, however, much less common with other mediums such as installation. The fact that the transfer from a unique work of art to a multiple is so uncommon in installation art is what makes the case of Phalli’s Field (1998) so interesting.

When Phalli’s Field (1965) was first created in the 1960s it was part of a temporary exhibition in a gallery. After the show ended, the work was not purchased and was eventually destroyed. Thirty years later it was re-created, and a new original was made for another temporary exhibition in the 1990s, this time in a museum. When this new original was created it was the only one in existence, unique, one of a kind – until another fifteen years passed and the 1998 work was remade in 2013. This time, however, the previous variant was still extant. Not only that, this new remake of the work was produced again and has ended up as an edition of three. A work that was once unique, the only one of its kind in existence, has seemingly become a multiple.

Untangling the multiple variants of 'Phalli's Field'

I have argued above that the 1998 variant of Phalli’s Field is both an original and an authentic work of art, not merely a copy of the 1965 version. The difference in layout of Phalli’s Field (1965) and Phalli’s Field (1998) constitutes a big enough change in the experience of the work to regard them as two different, original works. The 1998 work has value apart from its supposed status as a remake because, amongst other things, it is a blueprint for many later works that Kusama is now famous for.

If the 1998 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen variant of Phalli’s Field can be regarded as an original and authentic work, what does that mean for the newer variants of the work that were created and sold after 2010? The question as to whether Phalli’s Field (1998) is a unique work of art or a multiple is still unanswered. We can assume, since FLV was told they had purchased an editioned artwork number 2/3, that the work in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen’s collection is regarded by the studio and the gallery as number 1/3 because it seems that there are no other variants of the work that were sold before 2013. In line with this, it is also likely that the 1965/2016 Hirshhorn collection variant is number 3/3 in the edition. However, there is another theory worth exploring.

As I have said, hardly any differences can be found between the 1998 work and the post-2010 works. One of the differences is the dot pattern on the fabric of the catwalk in the 1998 work versus the post-2010 works. And although the 1998 originally did not have a ceiling, the studio has since confirmed that the work should not be shown without it.106 The variations between the individual new variants of the works, for instance between the 1965/2013 FLV work and the 1965/2016 Hirshhorn work are even less clear. In fact, there is no difference that can be easily spotted with the naked eye. The only difference that is easy to find is in the dimension of the floor space, and by extension the phalli covered panels, and even then, we can only speak of an insignificant variation of five centimetres.107

Although there are some differences between Phalli’s Field (1998) and the newer variants of the work, it is abundantly clear that these new variants are based on the 1998 work. Unlike the 1998 work, which was based on the one of 1965 (although with significant differences), the newer works share even less of a link with Phalli’s Field (1965), simply because the 1998 work already existed when they were made. When one combines this argument with the reading of Phalli’s Field (1998) as a new, original artwork, it would not be a stretch to conclude that the newer variants created after 2010 could be seen as copies of the 1998 work. Like many of Kusama’s post-2000 mirror rooms, the newer variants of Phalli’s Field follow the same principles as Phalli’s Field (1998). Unlike those other ‘Infinity Mirror Rooms’, however, the newer variants of Phalli’s Field are all almost exact copies of the interior of the 1998 work, because the same shapes, colours and materials are used. Despite the minor differences discussed above, almost none of which are visible to the naked eye, the experience that the visitor will have inside the room will be the same in each of the post-1998 works.108

It seems as though there are two options at the moment. Either the 1998 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen variant of Phalli’s Field is number 1/3 in a multiple with the works in the collections of Fondation Louis Vuitton and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; or the latter two works are copies of the 1998 work. Regardless of which argument one chooses to follow, it seems clear that Phalli’s Field (1998) has value as both an original and authentic artwork.

Conclusion

This article analyzed what the (re)creation and subsequent sales of multiple variants of Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) by Yayoi Kusama means for the variant of Phalli’s Field (1998) that is part of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen’s collection. The consideration of this case has led to the conclusion that the work in the collection of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen is both an original and an authentic work of art. Moreover, it has been argued that the creation of the post-2010 works and their sales, or the simultaneous existence of the various variants, do not in any way detract from the value of the work in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen collection. Nevertheless, the question as to whether or not the unique has become a multiple still remains.

Here the penultimate conclusion made will be revisited, namely that the work is either simply part of the multiple or that it should be seen as separate from the multiple, making the newer variants of the work copies of it. Looking at these two arguments side by side, it seems that the latter might be difficult to fully defend. It is obvious that for Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen this conclusion might be more favourable, because then the FLV and Hirshhorn copies do not diminish the value of their original. By contrast, creating new variants of the 1998 work and calling them a multiple does, as some of the unique quality of the work is lost.

So, to answer the question, ‘has the unique become a multiple’; it could be argued that yes, Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) has become a multiple. This has also been confirmed by the studio.109 But this does not detract from the value of Phalli’s Field (1998). This work, which has been in the collection of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen for ten years, is both original and authentic. It has value beyond the first 1965 variant of the work and also has qualities that the post-2010 variants of the work do not possess. Materially, Phalli’s Field (1998) is the oldest variant of the work still in existence. It was the basis for many later Infinity Mirror Rooms, and it tells an important story about Kusama’s rise to fame in the Western art world of the 1990s, as well as about broader developments in the history of installation art. This work should not only be seen as an original, authentic work of art but also as the primordial variant of all of the subsequent variants and the new post-2000 Infinity Mirror Rooms. Considering it a primordial variant sets it apart, even within the confines of an edition. Thus, in relation to previous and subsequent variants of the work, Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1998) in the collection of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen should be understood as an original, authentic work and the primordial variant within the multiple of the new Phalli’s Field, separating it from but also inextricably linking it to, all the extant and no longer extant variants of Phalli’s Field.

Credits

Author

Machteld Verhulst

Editors

Sandra Kisters

Esmee Postma

Lynne Richards

Website input

Eefje Breugem

Website technical support

Marieke van Santen

Archives

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Erik van Boxtel, Marieke Lenferink

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Jessica Gambling

Walker Art Center, Jill Vuchetich

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Claire Eggleston

Footnotes

1 Martinique, ‘Who Are The Most Successful Female Artists in Auction?’, accessed August 20, 2020, https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/most-successful-female-artists-in-auction & E. Kinsella, ‘Who Are the Most Expensive Living Female Artists?’, accessed August 20, 2020, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/most-expensive-female-artists-817277

2 K. Brown, ‘The Yayoi Kusama Craze Is Coming to Europe With a Splashy – But Nuanced – Three-Venue Retrospective’, accessed August 12, 2020, https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/yayoi-kusama-european-retrospective-1697466.

3 M. Yoshitake, ‘Infinity Mirrors: Doors of Perception’, in Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, ed. M. Yoshitake, Washington D.C. 2017, p. 12.

4 In the year that followed, Kusama debuted Kusama’s Peep Show (1966) in her third of three shows at the Castellane Gallery. This work again featured mirrors.

5 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 13.

6 The exhibition was shown at LACMA from 8 March to 8 May, 1998, at MoMA from 9 July to 6 October, 1998. The touring exhibition was closed out by an exhibit at Walker Art Center from 13 December, 1998 to 7 March, 1999.

7 Het Parool, ‘Boijmans Van Beuningen koopt werk van Kusama’, accessed December 2, 2020, https://www.parool.nl/nieuws/boijmans-van-beuningen-koopt-werk-van kusama~ba475009/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F & Trouw, ‘Boijmans Van Beuningen koopt werk van Kusama’, accessed December 2, 2020, https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/boijmans-van-beuningen-koopt-werk-van-kusama~b951384c/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F.

8 Sjarel Ex to Glenn Scott Wright, 7 March 2013, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen archive, object file on Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965-1998).

9 A.Verbeek (Sculpture Conservator, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden), email to the author, 14 September, 2020.

10 This research was carried out as part of an internship at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen for my master thesis of the same title. This article is the short form of the full-length thesis with some additional information provided by the studio, which was not given before the deadline for the thesis expired. The thesis can be found in the library at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

11 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, p. 69.

12 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, pp. 69-70.

13 I. Nakajima, ‘Yayoi Kusama between Abstraction and Pathology’, in Psychoanalysis and the image: Transdisciplinary perspectives, ed. G. Pollock, Oxford 2006, pp. 134-135.

14 M. Yamamura, ‘Kusama Yayoi’s Early Years in New York: A Critical Biography’, in Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York, ed. R. Tomii, New York 2007, p. 29

15 F. Morris, ‘Yayoi Kusama: My Life, a Dot’, in Yayoi Kusama: Obsessão infinita, eds. P. Larratt-Smith & F. Morris, São Paulo 2013, p. 201.

16 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, p. 82.

17 M. Yamamura, ‘Kusama Yayoi’s Early Years in New York: A Critical Biography’, in Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York, ed. R. Tomii, New York 2007, p. 35.

18 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, p. 83.

19 F. Morris, ‘Yayoi Kusama: My Life, a Dot’, in Yayoi Kusama: Obsessão infinita, eds. P. Larratt-Smith & F. Morris, São Paulo 2013, p. 201.

20 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 9.

21 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, p. 85.

22 M. Yamamura, ‘Kusama Yayoi’s Early Years in New York: A Critical Biography’, in Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York, ed. R. Tomii, New York 2007, p. 33.

23 M. Yamamura, ‘Kusama Yayoi’s Early Years in New York: A Critical Biography’, in Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York, ed. R. Tomii, New York 2007, p. 33.

24 M. Yamamura, ‘Kusama Yayoi’s Early Years in New York: A Critical Biography’, in Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York, ed. R. Tomii, New York 2007, p. 33.

25 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen has several of these Soft Sculptures in their collection, including Soft Washstand (1965).

26 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, p. 92.

27 S. Lee, ‘The Art and Politics of Artists’ Personas: The Case of Yayoi Kusama’, Persona Studies 1.1 (2015), p. 32.

28 S. Lee, ‘The Art and Politics of Artists’ Personas: The Case of Yayoi Kusama’, Persona Studies 1.1 (2015), p. 32.

29 S. Lee, ‘The Art and Politics of Artists’ Personas: The Case of Yayoi Kusama’, Persona Studies 1.1 (2015), pp. 31-32.

30 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, p. 94.

31 M. Yamamura, ‘Re-Viewing Kusama, 1950-1975: Biography of Things’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, eds. J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam /Dijon 2009, pp. 95-96.

32 Y. Kusama, ‘Overview of 1960s exhibitions’, accessed August 10, 2020, http://yayoi-kusama.jp/e/exhibitions/60.html & S.M.E. Jacobsen, ‘Biography’ in Yayoi Kusama: In Infinity, eds. L. R. Jørgensen, M. Laurberg and M.J. Holm, Humlebæk 2015, p. 117–118.

33 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, ‘Foto van Yayoi Kusama's installatie 'Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show' in de tentoonstelling 'Nul 1965', Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 1965, accessed April 24, 2021. https://www.boijmans.nl/collectie/kunstwerken/176794/foto-van-yayoi-kusama-s-installatie-aggregation-one-thousand-boats-show-in-de-tentoonstelling-nul-1965-stedelijk-museum-amsterdam-1965.

34 Y. Kusama, ‘Overview of 1960s exhibitions’, accessed August 10, 2020, http://yayoi-kusama.jp/e/exhibitions/60.html.

35 ‘Selected Biography and Exhibition History’, in Yayoi Kusama: Mirrored Years, edited by J. Guldemond and F. Gautherot, Rotterdam/Dijon, 2009, p. 291.

36 M.R. Sullivan, ‘Reflective Acts and Mirrored Images: Yayoi Kusama’s Narcissus Garden’, History of Photography, 39.4 (2015), p. 407.

37 P. Larratt-Smith, ‘Song of a Suicide Addict’, in Yayoi Kusama: Obsessão infinita, ed. P. Larratt-Smith & F. Morris, São Paulo 2013, p. 212.

38 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 13.

39 L. Zelevansky, ‘Driving Image: Yayoi Kusama in New York’, in Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama, 1958-1968, eds. L. Zelevansky and L. Hoptman, Los Angeles /New York 1998, p. 11.

40 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 2

41 Y. Kusama & R.F. McCarthy, Infinity Net: The autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, London 2020, p. 42.

42 J.B. Cutler, ‘Narcissus, Narcosis, Neurosis: The Visions of Yayoi Kusama’, in Contemporary Art and Classical Myth, eds. I. Loring Wallace and J. Hirsh, Farnham 2011, p. 99.

43 M. Yoshimoto, ‘Performing the Self: Yayoi Kusama and Her Ever-Expanding Universe’, in Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York, ed. M. Yoshimoto, New Brunswick 2005, p. 66.

44 Y. Kusama & R.F. McCarthy, Infinity Net: The autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, London 2020, p. 47.

45 M. Yoshimoto, ‘Performing the Self: Yayoi Kusama and Her Ever-Expanding Universe’, in Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York, ed. M. Yoshimoto, New Brunswick 2005, p. 66.

46 M. Chiu, ‘A Universe of Dots: An Interview with Yayoi Kusama’, in Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, ed. M. Yoshitake, Washington D.C. 2017, p. 168.

47 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 15.

48 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 81.

49 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 19.

50 J.Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 81.

51 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 81.

52 I was able to find only one image of Phalli’s Field (1965) that does not include Kusama. It features a small dog with spots on his coat, like the dots on the phalli.

53 J. Applin, Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room — Phalli’s Field, London, 2012, p. 15.

54 L. Zelevansky, ‘Driving Image: Yayoi Kusama in New York’, in Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama, 1958-1968, eds. L. Zelevansky and L. Hoptman, Los Angeles /New York 1998, p. 11. Kusama herself attended the openings at each of the three venues. This can be seen in images taken of Kusama at each of the venues.

55 I am indebted to Ms. Zelevansky for the contribution she has made to this research by so gracefully answering all of my questions surrounding 'Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama, 1958-1968'. The information she provided was of the utmost importance, filled in many blanks and made this article possible.

56 L. Zelevansky, email to the author, September 9, 2020

57 L. Zelevansky, email to the author, September 9, 2020.

58 Zelevansky, email to the author, September 9, 2020

59 Archive of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama, 1958-1968, EX.2182. March 1 - June 8, 1998. Box 59, Folder 19 'Kusama – Correspondence'. Fax from Yayoi Kusama to Lynn Zelevansky, dated November 2, 1997.

60 L. Zelevansky, email to the author, September 8, 2020.

61 Once more I must acknowledge the contribution of several individuals who made this research possible. The archivists of LACMA, Walker Art Center and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Jessica Gambling, Jill Vuchtich and Claire Eggleston.

62 Archive of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama, 1958-1968, EX.2182. March 1 - June 8, 1998. Box 59, Folder 19 'Kusama – Correspondence'. Fax from Yayoi Kusama to Lynn Zelevansky, dated January 29, 1997

63 The work was on loan from the Kusama studio. L. Zelevansky, email to the author, October 26, 2020.

64 Archive of the Sydney Biennale at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Communications around the installation of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Sydney on the occasion of the 12th Sydney Biennale in 2000. Fax from Linda Michael (MCA) to Dolla Merrillees (curator Sydney Biennale), dated April 11, 2000.

65 Archive of the Sydney Biennale at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Communications around the installation of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Sydney on the occasion of the 12th Sydney Biennale in 2000. Fax from Linda Michael (MCA) to Dolla Merrillees (curator Sydney Biennale), dated 11 April, 2000.

66 Archive of the Sydney Biennale at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Communications around the installation of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Sydney on the occasion of the 12th Sydney Biennale in 2000. Fax from Yayoi Kusama to Dolla Merrillees, dated 4 December, 2000.

67 B. van Lieshout (Head of the Technical Department at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) in conversation with the author, 19 September, 2020.

68 The work was purchased with the support of one of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen’s inhouse foundations, the Willem van Rede Foundation Fund. This foundation supports the museum in the acquisition of extra-ordinary works of international contemporary art made possible by a 1954 bequest.

69 Report of the 2010 installation of Phalli’s Field (1965-1998) at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Archive of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Object file on Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965-1998) BEK 1859 a-y (MK).

70 Over the years a camera was installed inside to work to allow for better surveillance and the work was given context by the addition of information in the space through which people had to walk to enter the work. Alongside the information, several photographs from the Boijmans collection of Kusama and her works taken by Theo Houts were shown.

71 Sjarel Ex to Glenn Scott Wright, 7 March 2013, archive of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, object file on Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965-1998).

72 N. Ogé (Curator Fondation Louis Vuitton), email to author, 16 November, 2020.

73 Archive of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. ‘Questions for Kusama studio’, in Dossier Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965-1998) BEK 1859 a-y (MK) ed. M.J. Verhulst, 2021, p. 115.

74 A. Verbeek (Sculpture Conservator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden), email to the author, 14 September, 2020.

75 J.H. Dobrzynski, ‘The Hirshhorn acquires a reconfiguration of Yayoi Kusama's first Infinity Mirror Room’, accessed August 15, 2020, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/hirshhorn-gets-yayoi-kusama-s-first-infinity-mirror-room.

76 Malba - Fundación Constantini, Buenos Aires (June 30, 2013 to September 16, 2013), Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro (October 12, 2013 to January 20, 2014), Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Brasilia (February 17, 2014 to April 27, 2014), Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo (May 21, 2014 to July 27, 2014) and Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, México (September 25, 2014 to January 19, 2015).

77 P. Larratt-Smith and F. Morris (eds.), Yayoi Kusama: Obsessão infinita, São Paulo 2013, p. 222.

78 The tour continued on to Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, Moderna Museet, Stockholm and Helsinki Art Museum.

79 L. R. Jørgensen, M. Laurberg and M.J. Holm (eds.), Yayoi Kusama: In Infinity, Humlebæk 2015, p. 124.

80 S. Kisters (Head of Collections and Research at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) to S. Goetze (Gropius Bau), August 21, 2020.

81 M.C. Vietzke (Exhibition Assistant at Gropius Bau) to S. Kisters (Head of Collections and Research at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen), 24 August, 2020.

82 Archive of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. ‘Questions for Kusama studio’, in Dossier Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show) (1965-1998) BEK 1859 a-y (MK), ed. M.J. Verhulst, 2021, p. 115.